Download pdf: The Storm

Isla de los Estados, 1902

When the ship’s silhouette was nothing more than a dot on the horizon, the sailor Novello knew that the captain would not turn back, and that certainty struck him like a blow and left him stunned: he had been abandoned on Isla de los Estados. His teeth chattered and his entire body began to tremble. No one would be coming for him. The ocean currents and the fog around the island were fearsome; they wrecked ships against the rocks as if they were empty barrels. In a fit of cowardice, he blamed his mother for everything. Six months earlier, sitting across from him at the kitchen table, his widowed mother had said, now that he was nearly twenty years old, he ought to enlist in the coast guard where, according to her, he’d “have a future”. And what a future! He looked around. It had snowed a few days earlier and good-sized patches of white carpeted the dark, rocky landscape. The mountainsides and fiords, covered in ferns and thick woods of coihue, displayed a somber beauty, but Novello did not notice it. Freezing to death, he instinctively took to walking, not knowing why or where he was headed.

Isla de los Estados, photograph from the blog Expedition Yahgan.

In truth, if Novello was now in a predicament it was because the San Juan de Salvamento Penitentiary was on the island. Or at least it had been till a week before, when the authorities decided to relocate it to Ushuaia and the prisoners, taking advantage of the situation, rioted and fled. In barges, they set off to cross Le Marie Strait with the aim of reaching Tierra del Fuego and their freedom. When the coast guard was notified, the base at Rio Gallegos where Novello was stationed dispatched a ship to quash the inmate uprising. But they arrived too late; the prisoners had already vanished with what was left of the prison staff in pursuit. The abandoned penitentiary, colder than the elements themselves, and the cemetery connected to the far wall, infused the sailors with superstitious fear; they felt it was an inhuman place, unfit even for murderers.

As if he couldn’t bring himself to accept what was happening, Novello went over their disembarkation on the island again and again. They had been given arms and ordered to comb a wide area around the penitentiary. In a confused allocation of manpower, he found himself forming part of a raiding party and got lost. Completely disoriented in the island’s desolate solitude, he could not find the way to the penitentiary. Hours later, he saw the ship pass before the cliffs, heading south, to Ushuaia. His post was in the hold; he realized that, even when they did notice him missing, they would not turn back. The captain knew, as well as they all did, that if the fugitives made it onto Fuegian soil, they would seek refuge in the estancias, and they were armed. Novello did not expect the ship to return for at least two or three days.

He was nonetheless fortunate, Novello thought, that they had been ordered to disembark with their knapsacks. He took quick inventory: two cans of meat, some biscuits, a knife, a length of rope and a few other items. He made his way down the cliff to the horseshoe-shaped beach where a colony of penguins nested. They barely noticed him, but Novello found comfort in seeing living beings that quacked and moved in that desolate place. He sat on a boulder and was eating a biscuit when a rock fell from behind him and rolled to the edge of the surf. He jumped up with his rifle at the ready and thought he saw a shadow disappear over the ridge. He tried to calm himself—Novello told himself aloud that he was nervous—and walked along the side of the cliff looking for refuge. After a short while, he came across the mouth of a cave in the rock. He inspected it and decided to camp there. He was carrying an armful of dry branches when he once again had the unmistakable sensation that someone was watching him from the cliff tops. He dropped the kindling, swung his rifle upwards and fired.

“Who goes there!”

The loud roar of the shot ricocheted off the steep creases of the coast and was eventually swallowed by the constant howl of the wind. Never before seen wild animals, some strange and furious creature of the island, took chaotic shape in Novello’s mind. He climbed desperately and, panting, stood facing the deserted hills with the large patches of snow that he had walked among hours earlier.

The shadows of twilight fell suddenly from the mountains and almost without any transition the island was submerged in profound darkness. Looking at the fire he had labored to light in the back of the cave, Novello felt all alone in this world, numbed by fear and cold. The wind’s mournful wailing rose and fell. He fanned the flames and made himself as comfortable as he could with a blanket over his shoulders. Fumbling in the layers of clothes he wore, he searched for the watch that hung on his chest, the only thing his father had bequeathed him: seven at night. It gave him weak comfort to know the time. It was something that still connected him to the others, to his home, his barracks. One of his shipmates, or his mother even, might be reading seven off some watch. By then, they must know that he had been left behind. In the midst of these thoughts, he lost track of the dimension of time.

When he awoke, the fire had been out for hours. With his body still stiff, he emerged into the gray light of a frigid morning that drove him to move and jump until he could feel the toes at the end of his feet once more. To the south, the sky foretold of a coming storm. In the distance he made out a dark shape that had caught his eye the day before, about a hundred meters from the mouth of the cave. He walked toward it. When he got there, he stood looking at the boat for a good long time. Its hull had been split and only half of it remained; it looked like the stern. The tide had swept it, overturned, far from the surf for who knew how long. Large iron bands with enormous rivets still kept the planks solidly joined. A few meters of rusty chain hung from a ring in the midst of a colony of limpets. A whaler from some ancient ship, an old sailboat, thought Novello, the remains of some shipwreck. It would make a good lid for the cave; it would protect him from the storm that was about to break at any moment now. He took off his knapsack, put his shoulder under the edge and pushed up. The hull, which was partly buried in the sand, barely budged a few centimeters. He got under it and, squatting, he curved his back and pushed. It took him tremendous effort, but this time the boat yielded just as a sharp pain ran through his hand. A nail in a protruding wood plank had pierced his left hand. He remained motionless, trying to gather up the energy to slip out from beneath the boat and wash his hand in the sea. When he stuck his head out from under the boat, a tall man was pointing the barrel of his own rifle at him. Novello perceived it all at once: the long mussed up hair, the days’ long beard, the filth, the striped garments of the penitentiary. The man wore a blanket on his head. From his sickly, bearded face, the man’s eyes, sunken and dull, stared at him fixedly. With the gun, he signaled for Novello to put his hands up. With his voice caught in his throat, he obeyed. The sea had become rough and the wind’s skittish whistling announced a fierce squall. The man clutched at the blanket that had blown off his head. Without a word, they both sought refuge under the boat. Novello saw the barrel of the gun close to his face, guarded by the prisoner’s sunken eyes. In a sudden impulse, he threw himself on his captor and struggled against a body that turned out to be nothing but skin and bones. The man was corpulent, but he barely defended himself.

“And now! What are you going to do … !” Novello shouted, once again the master of the rifle, which he pointed unsteadily at the prisoner, his arms transmitting his own trembling to the weapon. He crawled under the meager space beneath the boat and aimed at the escapee.

“Show me your hands! Put them together in front of you, I say!”

He tied the prisoner’s wrists with the length of rope and knotted a handkerchief over his wound. Regaining a bit of his composure, he took out the watch: twelve noon. Outside, the wind had died down. If he was lucky, he still had four or five hours of daylight.

“Get out,” he ordered.

He looked at the fugitive more closely. His initial fear having subsided, a comforting thought entered Novello’s mind. This unexpected turn of events would make him look good in the eyes of his commanding officer, not to mention his shipmates. Perhaps they would even give him a medal or some sort of reward. For a moment, he forgot where he was and gave himself over to the scene of a celebrated return to Ushuaia and Río Gallegos. His mother … the force of the wind pushed him forward, disintegrating these triumphal images. The sky was a dark purple and to the south, very low on the horizon, a milky splendor with livid edges signaled that there was no time to waste.

“Grab hold of the chain! Help me!” he ordered.

The prisoner obeyed and together they pulled until the half-boat came free from the sand and began to move. At the mouth of the cave, they both lay, panting, against the hull; with one final push, they managed to get it upright and lean it over the entrance. As soon as they recovered, Novello said:

“Got to gather firewood.”

The prisoner wrapped the blanket around his head and exited first. Low, black clouds flattened the contours of the island and hurried them without a word said between them. Back in the cave, ashen rays of light filtered through the planks of the dilapidated boat.

“Build a fire,” said Novello, tossing him the matches. He rested against the stone wall, exhausted, and pointed at the tin cup and the canteen that hung from a rope tied around the prisoner’s waist.

“Give them to me.”

The prisoner handed them over. Novello drank some water, put the cap back on the canteen and placed it beside him. Gusts of frigid air made the fire crackle as it grew larger, warming his legs and giving him the momentary illusion that everything would be all right. The prisoner had covered himself up with a blanket and stretched his hands toward the fire, which shone mercurial reflections on his gaunt face. To mask the anxiety he felt as the imminent storm approached, Novello took out a can of meat and set to opening it with the knife. The gun lay across his lap, the barrel pointed at the prisoner.

“I wonder what you did to end up here,” he mused aloud to cover up the sound of the wind. “I bet you killed a man, or a lot of men.”

He got the can open and held it near the fire. He looked at the prisoner and became emboldened.

“Answer me! Why are you here?”

And then the cave’s cold air got inside Novello’s bones because the prisoner, staring at him, opened his enormous mouth and showed him the stump that was left of his tongue. Novello’s jaw dropped. It took him a moment to recover from the shock.

“So they cut out your tongue … A snitch, are you … ” His voice trailed off and he was left scowling, looking at the can. What kind of man was he that they would do that to him? Novello did not like to think about it at all. Maybe it was an accident, he thought; the man had a scar on the side of his face that he had not seen earlier because of the beard. With a snort of impatience, he put some meat on two biscuits and handed it to his captive. The prisoner made it disappear in a second. Novello rummaged in his knapsack and his eyes lit up: the bag of yerba mate. He filled the tin cup with water and poured the yerba mate in it. Happily, he waited; maybe in the morning the ship would be off the coast. The hot mate tea was the best thing that happened to Novello since he had been left alone on the island. He handed the cup to the prisoner. A short while later, as if remembering he had something urgent to do, he took out his watch: six in the evening. A hollow shriek of wind announced the storm’s outbreak. Here it comes, he thought. He undid the dirty handkerchief and inspected the wound in his hand. He did not like how it looked.

Right then, the storm broke. Heavy rain and gale-force winds buffeted the hull, which shook furiously, showing that it was wholly insufficient. Novello shivered and tried to keep the fire alive. The waves of cold air became increasingly more intense and came out of the cave walls themselves. At one point that night, Novello no longer felt his feet. Much later, at least it seemed that way to him, the prisoner sat beside him and leaned into him. With his hands tied, he straightened out the blanket and the cape, covering both their backs. Their bodies together generated some heat. Outside, it seemed the entire island was being pulled apart. Novello buried his face in his arms, which were crossed over his knees, and in that position could see the half-boat trembling like a leaf in a hurricane, like a cardboard door shaking off its hinges. If the boat were blown away, they were dead men, he thought, without much concern in his muddled mind as his body cramped up and sleep overtook him, sinking him slowly into the darkness. Somebody shook his shoulder and he could barely lift his face. In the prisoner’s sunken eyes, Novello could see the reflection of the dying fire. The man thrust his hands forward. Novello could not feel his body; an irresistible need to sleep overtook him.

“Ah, you want me to free you … and then … ” His eyes closed.

The prisoner gestured frenetically, pointing at the entrance, and shook him again.

“Let me be.” Novello could barely move, and with great effort he aimed the rifle at the prisoner.

As if not caring if a bullet passed through him, the man threw himself on the rifle, the barrel sinking into his gut. A horrible, guttural sound came out of the fugitive’s throat; with a sweep of his hand, he took the weapon away from Novello and threw it on the other side of the fire. Taking hold of his captor by the shirt, the prisoner lifted him up brutally and pushed him towards the mouth of the cave, where he held his hands before the sailor’s face. Novello’s blood began to circulate once more; he was able to stand on his feet and muster the energy to pull out his knife. Feeling as if he were drunk, he clumsily cut the rope. Move the boat farther into the cave, the prisoner’s freed hands said. Deafening hail fell and the fire went out. In the darkness, unaware that he did so, Novello screamed. Feeling their way, shoulder to shoulder, they pushed, but the wind shoved them against the tumultuous trembling of the boat. Driven by the same instinct, they waited for a favorable blast of wind and, pushing at the same time, the boat was incrusted in the entrance. Right then, Novello felt a blow strike his head and lost consciousness.

When he awoke, flames made light and shadow move on the stone ceiling. He was lying face up, his cape covering him with the canteen under his neck. A sharp pain ran through his head. Concerned about his worrisome state, Novello forgot everything else. He touched his forehead and discovered some sort of bandage; it felt like cloth torn from a shirt. He lifted himself up on an elbow and looked around. Hailstones had formed a white band underneath the boat. Some entered the cave with such fury they bounced off its walls. The prisoner handed him the tin filled with mate tea. Taking it by the handle, Novello noticed that his hand had been cleaned and the dressing changed. His companion had taken advantage of the hailstones to melt them into hot water. But what had happened to him? He looked at the prisoner suspiciously and searched along the cave floor for the rifle. It was close to the fugitive, who was hunched over and covered with a blanket, apparently caring about nothing other than remaining as close to the fire as possible. Stealthily, with his pulse racing, Novello began to drag the rifle towards him with his foot, until it was within reach. A moment later, he was unsure of himself as he sat up and pointed the rifle at the prisoner, who seemed not to have noticed the stunt Novello had just pulled off.

“See here, you,” he said, trying to recover his commanding tone, but instead managing little more than a hoarse whisper. The man didn’t even look in his direction. “See here, you! What happened to me? Speak.”

He had forgotten that the prisoner was mute. Wearily, the man pointed to the boat and smacked his forehead with the palm of his hand. Novello felt horrible. Forgetting the rifle, he lay back down on the ground. He was going to die in that cave, wounded and cold. Never again would he see his mother or anyone else. Self-pity took hold of him; he gripped the watch and gave a look at the time; he wept silently, unaware that he was crying. He felt a hand squeeze his shoulder and pat his back. The prisoner made signs in the air, as if wanting to say: We’re leaving. In a daze, Novello interpreted the signs as meaning they were going to die right then and there, and his face contorted in fear. The prisoner shook his head. He made another sign to indicate sliding the boat away from the entrance and heading out into the sun, into life. Novello composed himself and, not knowing when exactly, fell asleep.

In the morning, the storm had passed. Low clouds swept towards the north at great speed; the cold cut their faces and the land was white with hailstones where the ground was uneven. Down by the beach, the penguin colony had once again settled in, which Novello took as a good sign. Without a word, he tied the prisoner’s hands, who stretched them out to him without resisting. He pointed the rifle at him and they left the cave. A short while later, they had made it to the top of the cliff. Just after midday, the coast guard ship cut its silhouette on the horizon. Novello went wild, jumping and running and spinning around, waving his arms. Throughout this display, the prisoner remained still, sitting on a rock with his head bowed under the blanket.

“They’ve seen us! They’re coming!” shouted Novello, jumping excitedly.

Then he calmed down and also sought out a rock to sit on. For a long while he looked out to sea. He looked at the prisoner and then looked out to sea again, as if he were weighing the pros and cons of a decision. At last, he took his knife out of its sheath and approached the prisoner slowly. He tapped him to lift up his hands and signaled his intention to cut the rope. Not knowing why, Novello had adopted the hand signaling of the mute: with his hands Novello told him he could leave, that he would set him free. The other shrugged his shoulders and, with a slight smile, shook his head. It’s true, thought Novello, where could he go; he’d be dead in two days, and as a natural and immediate consequence of this realization, he also thought, And I would be, too, had I been alone. Snapping out of the shock of his abandonment on the island, for the first time he clearly understood something that the prisoner surely knew from the beginning: that they were alive because they were two; that in that icy wasteland, a lone man did not stand a chance. And if the prisoner had stalked him from the cliffs it was simply because the ship would come back for him, because just like Novello he wanted to survive. When this became clear to him, Novello stepped back and sat on his rock, and the solitude he again observed all around him seemed even more terrible and savage. Four hours later, they were brought onboard.

Bewildered by his instant celebrity, Novello forgot all about the prisoner, who was taken into custody and escorted below deck. The enthusiastic voices of his shipmates, between words of praise and pats on the back, asked him for the details of his adventure. For the first time, Novello was the center of a circle of friendly, smiling faces that passed around a bottle of cane brandy. As he took eager gulps and showed off his injuries, which he downplayed although he found them incredible himself, he repeated the tale of his encounter with the fugitive, who, without realizing it, he had already begun to magnify. It wasn’t until sundown, when Novello went below deck to resume his post, his head swimming slightly, that he remembered the prisoner. The man of flesh and bone, not the ferocious escapee of his tale. In the cabin that served as a cell, a draftee guarded him. Novello stood by the door. He experienced a vague feeling that he could not put his finger on. Irrepressible words formed in his mouth:

“We made it, eh?”

The prisoner looked at him with the slightest of irony, which Novello was in no condition to pick up on. Impulsively, he lifted up the bottle of cane brandy and, signaling the guard to leave them—the soldier obeyed; after all, the order came from the hero of the day—he offered it to the prisoner. The man grasped it with his bound hands and took unhurried swigs that seemed to never end. When at last the prisoner left the bottle on the table, Novello found he had nothing more to say. He was about to leave when, of their own accord, Novello’s hands went to pat the man on the back. The patting also seemed to never end. The prisoner looked at him, blankly. And that was all. A short while later, in his bunk, Novello began to doze off to the rhythm of the familiar murmur of the ship’s engines. Beforehand, he had not glanced back, not even once, to see the somber silhouette of Isla de los Estados which, to stern, disappeared in the gray mist of nightfall.

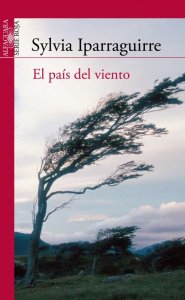

Translated by Dario Bard from a manuscript of “La Tormenta” provided by the author and which later appeared in the newspaper Pagina12. The story first appeared in El país del viento published by Alfaguara in 2003, available from Amazon.

Sylvia Iparraguirre was born in Junin, Province of Buenos Aires, and lives in the City of Buenos Aires. Early in her literary career, she wrote for the literary magazine “El Escarabajo de Oro” and later co-founded “El ornitorrinco”, a literary magazine that was published from 1976 to 1986. Iparraguirre has written several short story collections and novels, including Tierra del Fuego, a historical novel available in English based on the life of Jemmy Button, a member of the Yamana people from Tierra del Fuego who was captured, taken to England, converted to Christianity and later returned to his native land by Captain Robert Fitzroy of the HMS Beagle.

Iparraguirre has received several awards recognizing her literary contributions. Most recently, in 2014, the prestigious Konex Foundation recognized her as one of Argentina’s best novelists for the period 2011 to 2013.

On the Argentine television program, Obra en Construcción, Sylvia Iparraguirre discussed her literary career (in Spanish):

Part 1

Part 2